Ur was a city in the region of Sumer, southern Mesopotamia, in what is modern-day Iraq. According to biblical tradition, the city is named after the man who founded the first settlement there, Ur, though this has been disputed.

The Great Death Pit at the ancient city of Ur, in modern-day Iraq, contains the remains of 68 women and six men, many of which appear to have been sacrificed.

Dating back about 4,600 years, a variety of fantastic treasures, including a statuette known as the Ram in the Thicket, which is made of silver, shell, gold, lapis lazuli and carnelian, were found in the death pit. Archaeologists believe that the pit was used to bury Ur’s rulers.

The city’s other biblical link is to the patriarch Abraham who left Ur to settle in the land of Canaan. This claim has also been contested by scholars who believe that Abraham’s home was further north in Mesopotamia in a place called Ura, near the city of Harran, and that the writers of the biblical narrative in the Book of Genesis confused the two.

Whatever its biblical connections may have been, Ur was a significant port city on the Persian Gulf which began, most likely, as a small village in the Ubaid Period of Mesopotamian history (5000-4100 BCE) and was an established city by 3800 BCE continually inhabited until 450 BCE. Ur’s biblical associations have made it famous in the modern-day but it was a significant urban center long before the biblical narratives were written and highly respected in its time.

The site became famous in 1922 CE when Sir Leonard Wooley excavated the ruins and discovered what he called The Great Death Pit (an elaborate grave complex), the Royal Tombs, and, more significantly to him, claimed to have found evidence of the Great Flood described in the Book of Genesis (this claim was later discredited but continues to find supporters).

In its time, Ur was a city of enormous size, scope, and opulence which drew its vast wealth from its position on the Persian Gulf and the trade this allowed with countries as far away as India. The present site of the ruins of Ur are much further inland than they were at the time when the city flourished owing to silting of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

In the Old Babylonian Period (c. 2000-1600 BCE) Ur remained a city of importance and was considered a centre of learning and culture. According to the historian Gwendolyn Leick, “The `heirs’ of Ur, the kings of Isin and Larsa, were keen to show their respect to the gods of Ur by repairing the devastated temples” (180) and the Kassite kings, who later conquered the region, did the same as would the Assyrian rulers who followed them.

The city continued to be inhabited through the early part of the Achaemenid Period (550-330 BCE) but, due to climate change and an overuse of the land, more and more people migrated to the northern regions of Mesopotamia or south toward the land of Canaan (the patriarch Abraham, some claim, among them, as previously noted). Ur slowly dwindled in importance as the Persian Gulf receded further and further south from the city and eventually fell into ruin around 450 BCE.

The area was buried under the sands until it was visited by Pietro della Valle in 1625 CE who noted strange inscriptions on bricks (later identified as cuneiform script) and images on artifacts which were later recognized as cylinder seals used to identify property or sign letters. In 1853 -1854 CE the first excavation of the site was made by John George Taylor in the interests of the British Museum who noted multiple grave complexes and concluded the site may have been a Babylonian necropolis.

The definitive excavation of the ruins of Ur was conducted between 1922-1934 CE by Sir Leonard Wooley, working on behalf of the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania. The famous Tomb of Tutankhamun had been discovered by Howard Carter in 1922 CE and Wooley was hoping for an equally impressive find. At Ur he uncovered the graves of sixteen kings and queens, including that of the Queen Puabi (also known as Shub-ad) and her treasures.

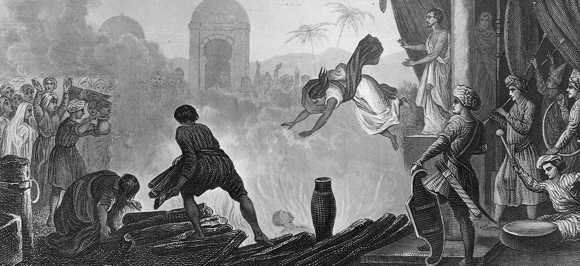

The Great Death Pit, as Wooley named it, was the largest of those uncovered and, in it, “Wooley found six armed guards and 68 serving women. They wore ribbons of gold and silver in their hair, except one woman who still held in her hand the coiled-up silver ribbon she was unable to fasten before the sleeping potion took hold that painlessly carried her away to the afterworld with her master” (Bertman, 36).

Wooley also uncovered the Royal Standard of Ur which celebrated the city’s triumph over her enemies in war and the festivities which the people enjoyed in peace. In an effort to out-do Carter’s triumph in the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb, Wooley claimed that he had found evidence at Ur of the biblical Flood but notes taken by his assistant, Max Mallowan, later showed that the flood record at the site in no way supported a world-wide deluge and was more in keeping with the regular flooding caused by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers

Further excavations at Ur since Wooley’s time have corroborated Mallowan’s notes and, in spite of persistent beliefs to the contrary, no evidence supporting the Great Flood story from the Bible has been found at Ur nor anywhere else in Mesopotamia. Still, as Bertman notes:

Even if stripped of its biblical claims to fame, Wooley’s Ur is still a glittering example of Sumeria’s golden age. Though its original lyres no longer sound, with our inner ear we can still hear their melodies.

The ruins of Ur today are a significant archaeological site which continues to yield important artifacts when the troubles of the region allow. The great Ziggurat of Ur rises from the plains above the mud-brick ruins of the once-great city and, as Bertman suggests, in walking among them one relives the past when Ur was a center of commerce and trade, protected by the gods, and flourishing amidst fertile fields.